In Belgium, every year, nearly 75.000 patients are diagnosed with cancer. That’s 205 patients a day, 9 patients an hour.1

In this paralyzing moment, patients are overwhelmed by a tsunami of emotions. Dreams that were preoccupying their life minutes before, suddenly recede far into the background.

All life goals can be merged into 1 word: surviving. A terrifying arena will be entered, which they hope to leave unharmed. Fortunately, life expectancy has increased tremendously due to advances in cancer treatment and early detection.2 However, an important portion of the cancer survivors are left with marks that are too often experienced as scars.

One out of three women will experience above-average pain following breast cancer treatment.3 The high prevalence is of a considerable concern due to the fact that pain is a malefic force that not only infringes the patients’ day-to-day functioning and quality of life, but is also seen as a constant reminder of their cancer history.4 Therefore, pain is a condition that should be routinely addressed as a part of the patients’ survivorship care when appropriate.

Knowledge about the risk factors for the pain development is not only of a crucial matter for the improvement of its prevention, but also for the implementation of the best possible treatment strategies. In pain research we are facing large inter-study variability due to a lack of uniformity in the definition of pain and the shortage of a golden standard for the diagnosis of pain in cancer survivors. Therefore, meta-analyses are imperative in order to come forward with strong conclusions regarding the factors that might put cancer survivors at risk for the development of pain.

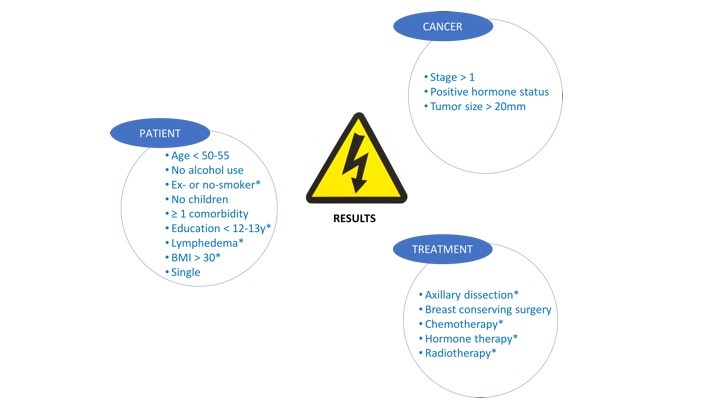

Our results revealed that patients with a Body Mass Index higher than 30, lymphedema, a lower education level, non-smoking status, being exposed to axillary lymph node dissection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy during treatment are at a significantly higher risk for developing chronic pain.5 To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates direct evidence for the link between lymphedema and the development of pain symptoms.

During survivorship, surveillance for recurrence and vigilance for new cancers are top priority. However, one should be aware that while being so focused on recurrence, health care takers and patients are at risk of neglecting other aspects of their health status. Furthermore, a so-called response shift may occur in cancer survivors, which is characterized by a reconceptualization of the internal reference framework for the evaluation of their health condition.6-8 Suddenly, the little things make life big. This might result in underreporting of health concerns that can have a more immediate and debilitating outcome.

We as clinicians cannot change the cards our patients are dealt with, just how to play the hand…

Laurence Leysen

Member of the international Pain in Motion research group.

PhD researcher and assistent teacher at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium.

2017 Pain in Motion

References and further reading:

1. Registry BC. Belgian Cancer Registry, Females and males, age-specific and age-standardised incidence rates of cancer, by primary site in 2014 (n/100,000 person years) Available via http://www.kankerregister.org/.

2. Cancer IAfRo. World Cancer Report. Lyon, 2014.

3. Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, George SM, et al. Pain in long-term breast cancer survivors: the role of body mass index, physical activity, and sedentary behavior. Breast cancer research and treatment 2013; 137(2): 617-30.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23242613

4. Bokhari F, Sawatzky J-AV. Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Women After Breast Cancer Treatment. Pain Management Nursing 2009; 10(4): 197-205.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19944375

5. Leysen L, Beckwee D, Nijs J, et al. Risk factors of pain in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2017.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28799015

6. Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Eaton HM, Phillips CB, Liang MH. Discrepancies between self-reported and observed physical function in the elderly: the influence of response shift and other factors. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48(11): 1549-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10400256

7. Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA. Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48(11): 1531-48.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10400255

8. Cella D, Bullinger M, Scott C, Barofsky I. Group vs individual approaches to understanding the clinical significance of differences or changes in quality of life. Mayo Clin Proc 2002; 77(4): 384-92.